JAPANESE ART SONG

日本歌曲

Japanese Lyric Diction

It would be safe to say that Japanese is one of the easiest languages to sing in. Rōmaji (Romanized transliteration) is phonetic, much like Italian, Spanish, and Latin. There are only five vowels, which are all pure vowels. Once you learn some rules and tips, singing in Japanese would become surprisingly easy.

QUICK TIPS

-

Sing pure vowels, except for u (with slightly horizontal lips), and keep a legato line as in Italian songs.

-

Sing evenly as in French songs.

-

Don’t aspirate consonants too much in [k], [g], [s], [z] [t], [d], [p] and [b], but clearly.

-

Don’t anticipate or elongate consonants f, m, n, r, w, y, and especially [ŋ].

-

However, put a slight emphasis at the beginning of important words.

-

Enjoy singing an elongated n when it is an independent syllable.

-

Most of letter g’s are soft and nasalized [ŋ].

-

Don’t use American r’s, but don’t roll r’s either. Flip r quickly and lightly in the front of the mouth.

-

Know the meaning of each word and don’t breathe in the middle of a word or before a particle.

Please read the following sections for more details of Japanese Lyric Diction:

SYLLABLES

RŌMAJI AND IPA (Vowels and Consonants)

SPECIAL NOTES ON CONSONANTS (Double Consonants, fu, ng, and n)

VOWEL OMISSION

GLOTTAL STOPS

SYLLABLES

One of the most important aspects of Japanese poetry is the number of syllables in each line. This is much like French poetry, in which the number of syllables in each line defines the form of the poem: for example, Alexandrine is a form that has twelve syllables in each line.

Two most known Japanese poetic forms are:

Haiku Three lines. Number of syllables in each line is 5-7-5.

Tanka (Waka) Five lines. Number of syllables in each line is 5-7-5-7-7

Tanka means “short song” and Waka means “Japanese song.” There are many Japanese art songs in the Western music style that are set to tanka poems, while Haiku poems have not been very popular among Japanese composers most likely because Haiku poems are too short. Many other Japanese song texts use 5-7 or 7-5 patterns.

Please note that every Hiragana or Katakana character is counted as a syllable. Some important concepts for syllable counting include:

-

Japanese has long vowels and short vowels. Long vowels are count as two syllables and indicated with tenuto signs in Rōmaji.

koko (ここ)–2 syllables kōkō (こうこう)–4 syllables (sung as [kɔ: kɔ:], not [kɔu kɔu] )

2. ん/ン(n) is sometimes considered as a “half vowel”, and is counted as a syllable, in which case it must be sustained with a pitch.

hana-no en (はなのえん)–5 syllables minna (みんな)–3 syllables

3. A stoppage created by a small つ/ツ(tsu) indicates double consonants, and it is counted as a syllable.

ippai (いっぱい)–4 syllables petto (ぺット)–3 syllables

RŌMAJI and IPA

Rōmaji is phonetic and easy to read. By knowing some differences between Rōmaji and IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet), you are ready to pronounce Japanese words easily.

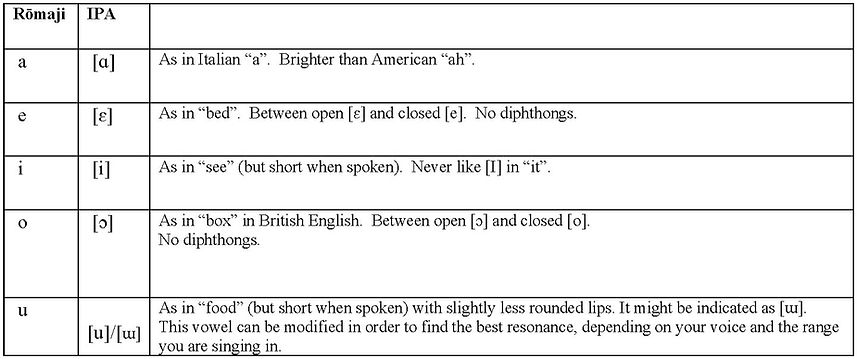

VOWELS

Japanese vowels are simple and pure. They are usually bright and must be placed forward in the mouth as in Italian. However, the letter u could have slightly less rounded lips than the pure [u].

CONSONANTS

Japanese consonants are short and crisp, and without much aspiration. However, initial consonants of important words should be emphasized with slight aspiration or elongation.

Most consonants are easily figured out from Rōmaji. Some consonants that need attention are as follows:

SPECIAL NOTES ON CONSONANTS

Double Consonants

Japanese double consonants that are indicated in Rōmaji must be treated similarly to Italian double consonants. In Japanese versification, a stoppage created by double consonants is counted as one syllable. Some composers insert a short rest for this purpose, but if there is no rest, singers must create a brief pause.

Example: “tomatte” → “toma te”

fu

Traditional Japanese language does not have the [f] sound, but in the most common Rōmaji writing (Hepburn romanization) [fu] is used to transcribe ふ/フ(hu). This consonant is a bilabial fricative [ɸ] and could be described as a sound that is halfway between [f] and [h]. This sound could be indicated as [ɸɯ]. However, many Japanese classical singers use [f] for easier projection of the sound, especially when it is at the beginning of an important word. You may use [f], [h], or [ɸ] with [u] vowel or [ɯ] vowel in singing.

ng [ŋ]

In the most authentic spoken and sung Japanese, it is proper to pronounce letter g as a soft and nasal sound [ŋ] in the particle “ga” and when it occurs in the middle of a word except in combined words and numbers. (This convention is not used in the west side of Japan, and the younger generation of Japanese people may not be trained to speak in this way.) This must be executed very rapidly and never be anticipated or elongated when it is followed by a vowel. However, you must elongate it when [ŋ] is substituted for [n], including a syllabic n before a vowel.

Example of short [ŋ]: “Onagori oshiya, Kurai namima-ni yuki-ga chiru” (Defune)

Example of long [ŋ]: “Aki jinˀei-no” [ɑki dʒiŋˀɛi nɔ] (Kōjō no Tsuki)---“n” could be sung as [ŋ], and is elongated.

For singers struggling with the short [ŋ] sound, substituting it with the Spanish soft fricative “g” [ɤ] would be acceptable.

n

Aside from the notes on the consonants chart above, one more thing to be careful of is that, when a sustained letter n is at the end of a note, but preceded by another syllable, it must have a half of the note value.

Example: Tenjō kage-wa (from “Kōjō no Tsuki”)

“Ten” is set to a quarter note. In many other languages n must be sung at the very end of the quarter note. However, in Japanese singing, the n should occupy the full length of an 8th note since it has a full value of one syllable.

(Written ) Ten → (Sing) Te–n

♩ ♪ ♪

VOWEL OMISSION

In the standard spoken Japanese, vowel sounds “i” and “u” are often omitted after unvoiced consonants (such as k, s, h, sh, ts, etc.) in an unstressed syllable; for example, a verb ending “desu” would sound as “des”. (This may not happen in the west side of Japan.) In singing, using this technique is not always recommended. However, when such a syllable occurs on a repeated short note, especially where a speech-like presentation is desirable, it is possible to omit a vowel sound and still sustain the note only with the consonant sound. A very important tip for this technique is to shape the lips according to the original vowel without voicing it.

Vowel omission is indicated by parentheses in the rRōmaji transcription in this website.

Example 1: “yasash(i)katta yo”

Here, your lips are shaping the [i] vowel, and you will elongate the consonants without phonating the vowel sound.

Example 2: “nats(u)kashii”

With your lips, make sure to form a slightly lateral [u] shape, but elongate the consonants [ts] without phonating the vowel.

GLOTTAL STOPS

When a new word starts with a vowel within a phrase, some Japanese singers choose to use a glottal stop.

Example: hana no ˀen (a glottal stop before “en”)

As in other languages such as German and English, usage of glottal stops must be executed with utmost care and sensitivity. In Japanese songs, a gentle glottal stop or a small lift without glottal attack would suffice most of the times, saving strong glottal attacks for dramatic moments.